I am out of practice at writing here, let’s see how this goes.

My last post was 14 months ago for all sorts of reasons, most of which have to do with the fallout of the pandemic. The spring of 2020 was sheer chaos as we were all trying to figure out how to teach virtually. The 2020 – 2021 academic year saw a multitude of rules restricting how we could interact with each other when we were in person (which, for our school, was the great majority of the year) and a couple of retreats into virtual schooling. I had students in front of me and students on my computer screen all year long (at least when we could have people in the same room!) and I know I was not alone in learning how to deal with that. I had all my students seated in rows and columns for the first time in 15 years and I had to try to relearn how to look out at a class like that. We could not sit in groups and share ideas with our neighbors at our elbows. I could not roam around the room and look over people’s shoulders and quietly share ideas and questions. None of this is news to anyone who is reading this. What I am trying to figure out is what tools/habits I’ve developed in the past fifteen months are worth carrying forward into the 2021 – 2022 academic year and beyond. There is a cliche about not wasting a crisis and I had some pretty meaningful conversations with my students about the ‘new normal’ this year. I laid out some practices that I had adopted, practices that were not part of my repertoire before COVID days. I asked them what was worth keeping and what they would be happy to never deal with again. The three features of life this year that got the biggest endorsements were (1) Scanning and submitting written work so that they could access their work and my comments at a later time. (2) My inclusion of DeltaMath into our life. (3) My use of BitPaper for classroom notes.

I want to think out loud about each of these three features.

1 – Obviously, any paper submitted and returned with notes/corrections/remarks is retrievable, even in COVID times. However, my students were really honest about their lack of organizational skills. Most papers that ever got returned got shoved into backpacks, ended up at the bottom of a locker, on the floor of their car or their bedroom, and were not accessible when it came time to study or reflect. I did not enjoy writing on their work through the google classroom and within the Kami environment. But if even a small portion of my students actually went back to the Google classroom page later to reflect, then it might (might!) be worth that time and effort.

2 – I was way too late to the DeltaMath game. I think Zach’s work there is tremendous and I got so much positive feedback from kids about the guided practice and videos available to them there (I paid for a plus membership so my students have limitless (I think it is essentially limitless) access to carefully presented videos to help them work out mechanical issues and to be reminded of why math life was unfolding the way that it was.

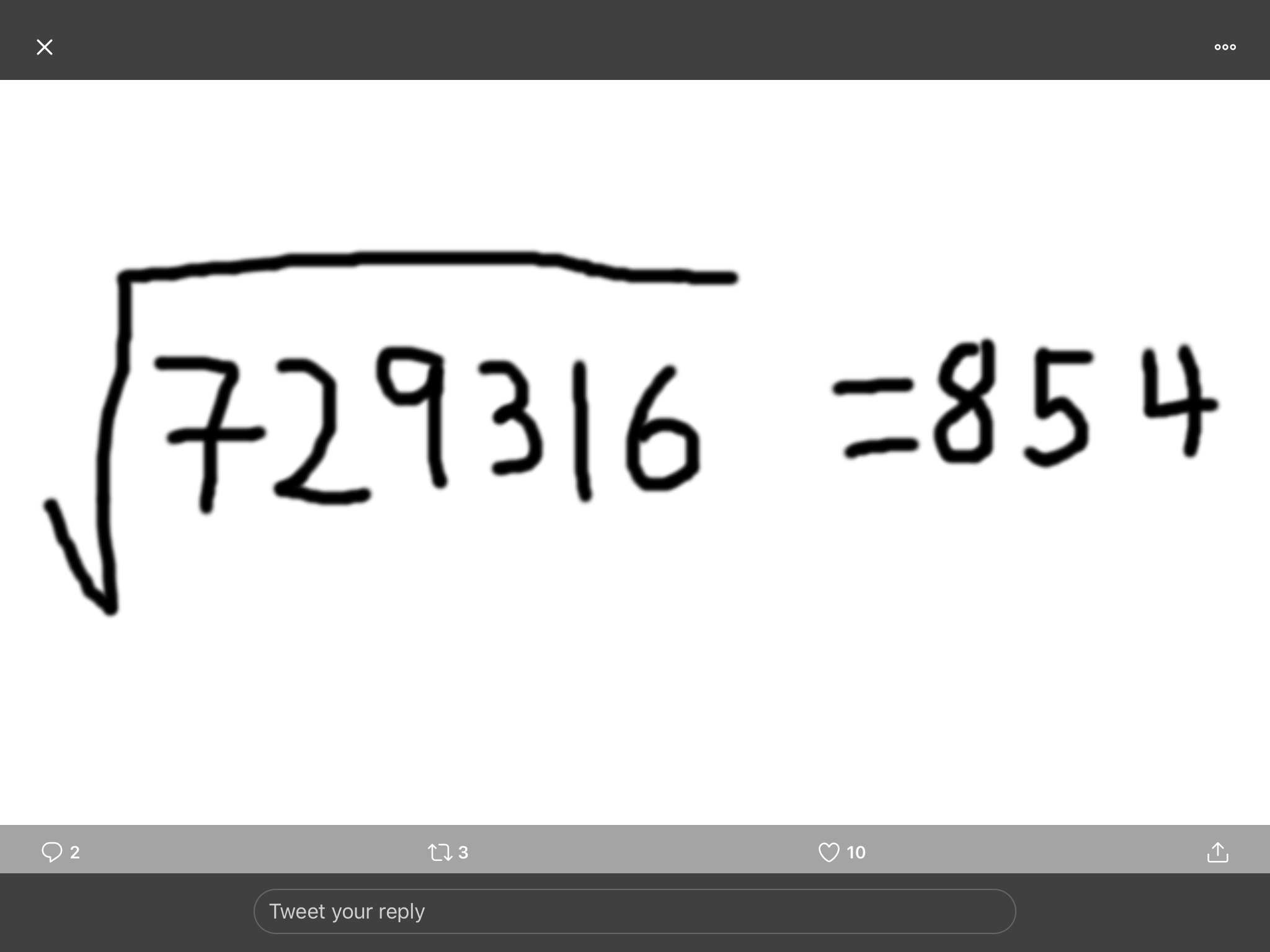

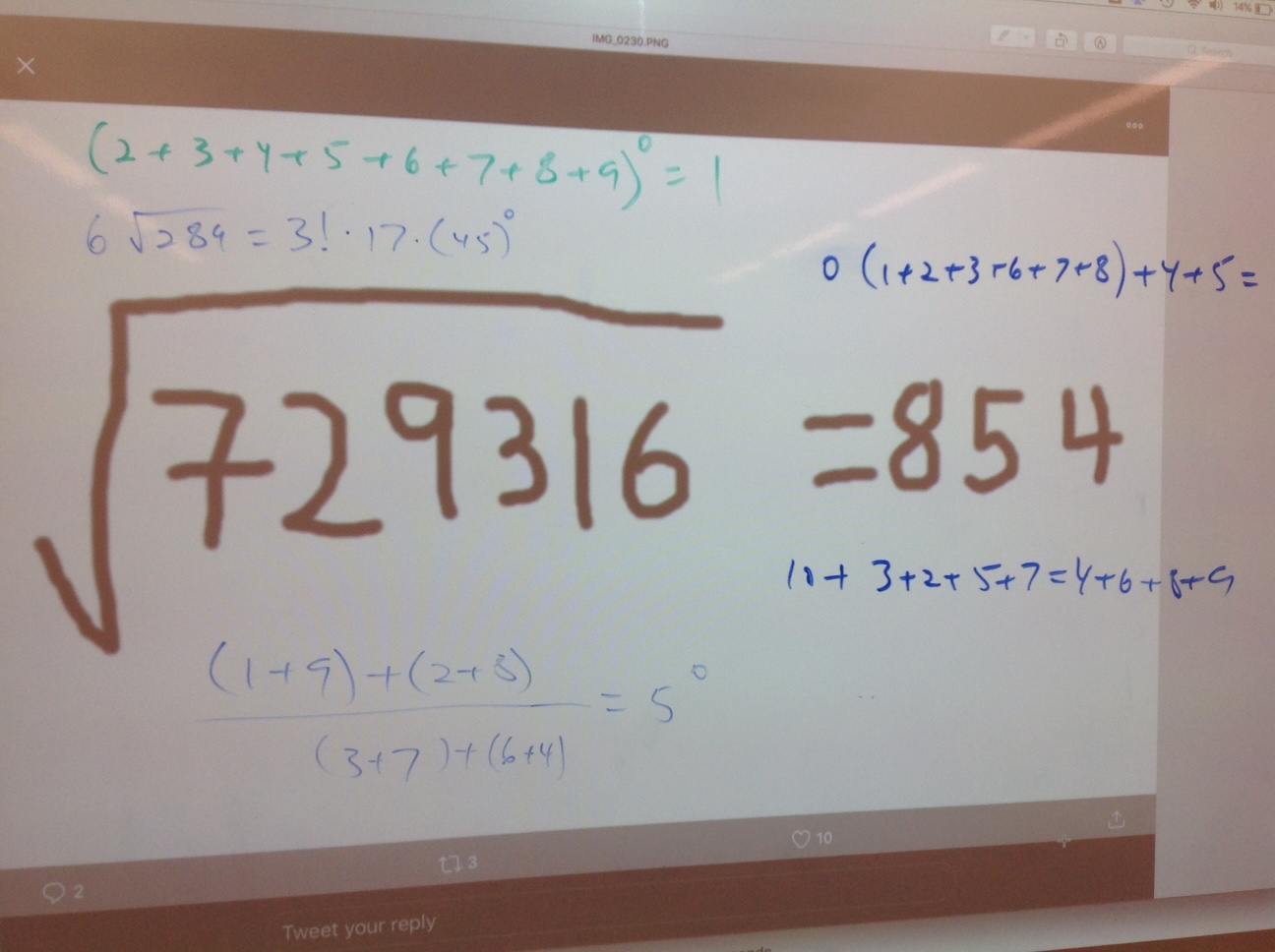

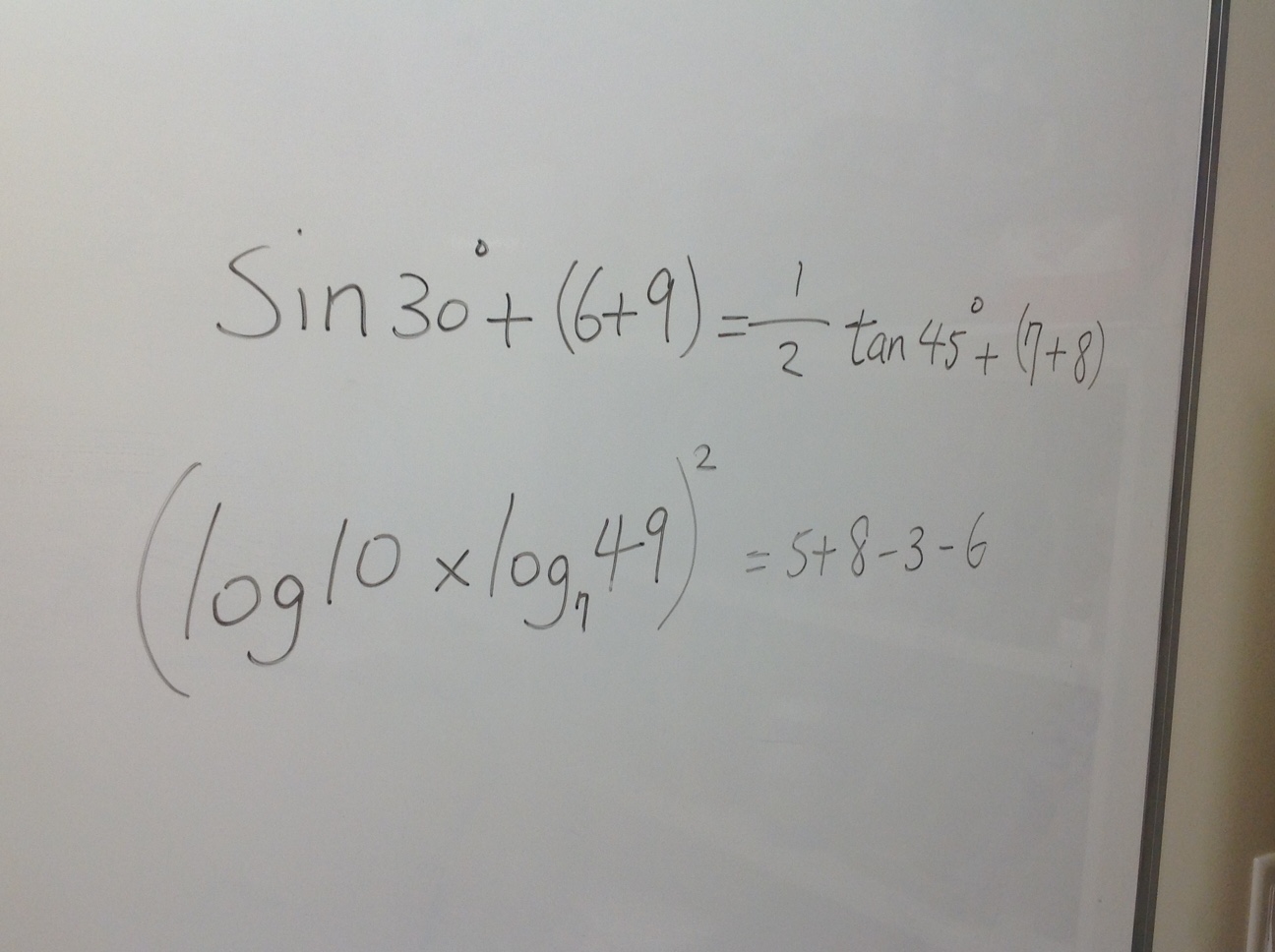

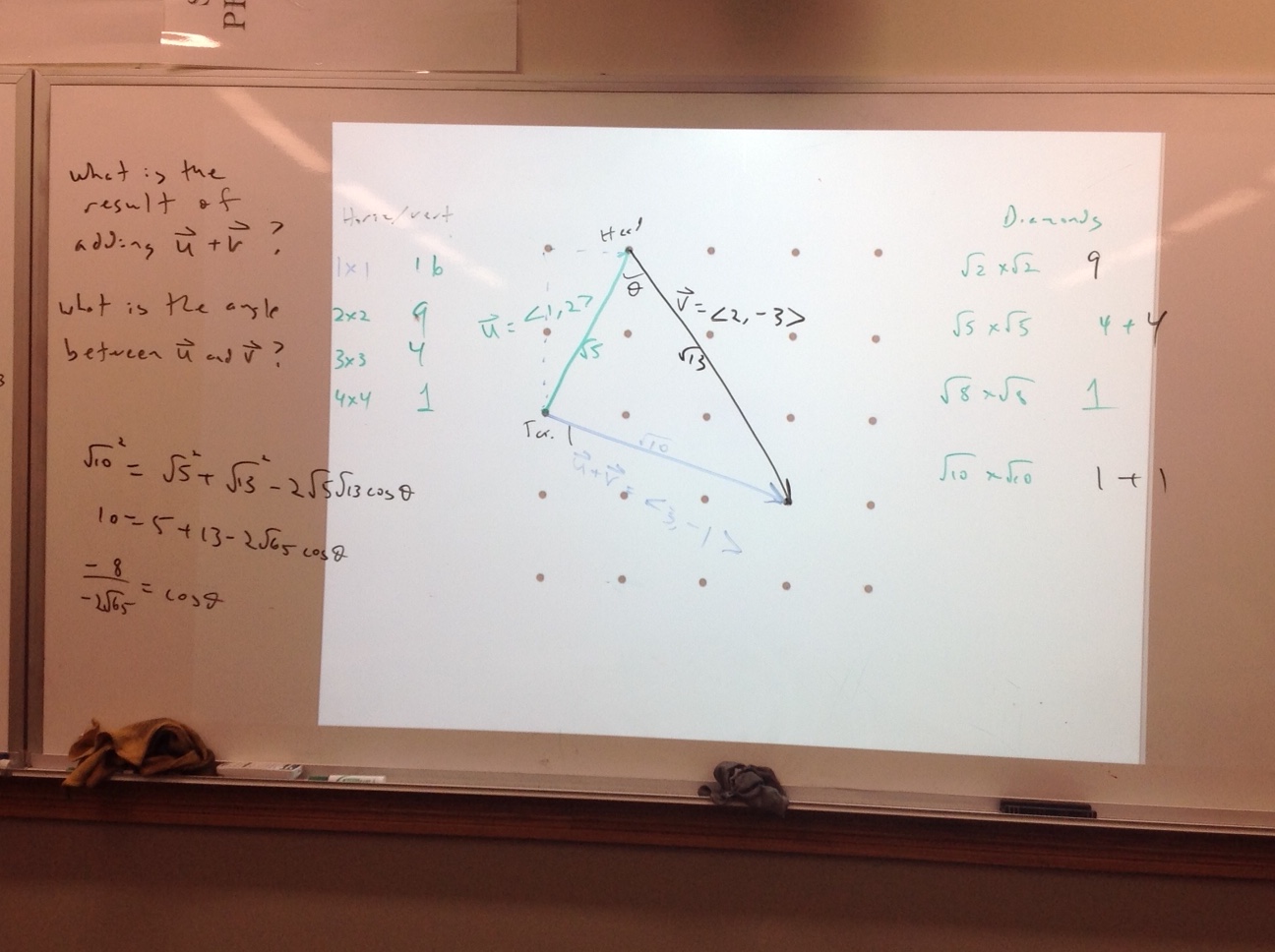

3 – I don’t know how many people know this tool. Here is an example of one of my BitPaper note pages https://bitpaper.io/go/Bell%206%20Calc%20Hon%20Week%20of%20May%2010/HJpuKAieh

I set up a new page for each section each week so that the pages would not get TOO cluttered. I did not write on a whiteboard at the front of the room at all this year. I did all of my writing on BitPaper and students had access to these pages at any time. There are some tweaks I wish they would make. I wish there was a scroll bar to move up and down the page. I wish multiple kids could view at the same time without interrupting each other. The second wish might be a lack of understanding on my part. But that is not what I want to write about. I want to talk about what I see as a huge advantage. My students can listen in on my conversation and what their classmates are saying. They can jot down quick notes or reminders to themselves, but they do not have to feel any pressure at all about transcribing while listening. They can look at class notes later and listen and think more efficiently in real time. I had a discussion about this tool and about the fact that I intend to use it again next year (or a different tool that might be better if someone can steer me to one!) and the response I got was that note taking is a vital skill and they need to work on this. I tried not to react negatively but inside I was sure feeling some serious skepticism about this claim. It feels obvious to me that listening and thinking and talking are more important than being a stenographer. If I am wrong here, if I am missing something important, I hope to hear it either in the comments or over on twitter where I am @mrdardy

There were SO many new tricks/tools that I tried this year but these three were the ones that resonated with my students. I would love to hear some reaction to these ideas and also hear about successful new tools/ways of thinking that infected your classroom during the pandemic.